For consistency, Wallace will be referred to “he” throughout this article. Wallace uses he/they/ze pronouns.

Lewis Raven Wallace, an independent journalist who has previously worked at outlets including NPR, took the stage last Friday at the Cosford Cinema to pose a question to UM’s School of Communication — does neutrality still have a place in journalism?

Wallace is the first abolition journalism fellow for Interrupting Criminalization, an initiative that aims to end the criminalization and incarceration of marginalized groups, and the author of “The View from Somewhere,” a book on the history of journalistic objectivity and how it has historically served to “uphold the status quo and exclude voices from oppressed communities.”

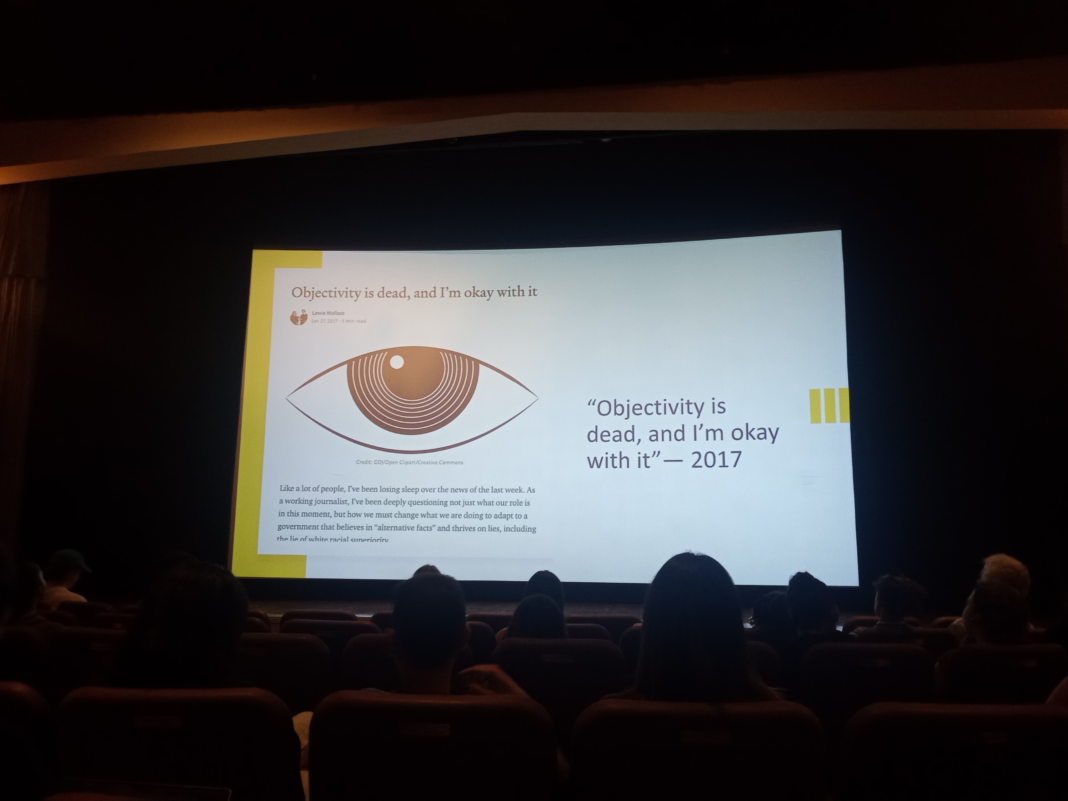

Wallace lost his job in public radio in the wake of the 2016 presidential election, after he wrote a blog post calling for journalists to practice journalism with a purpose, as well as to rally to protect democracy.

“For anybody who brings moral convictions and a clear sense of values to the practice and trade of journalism, especially in the context of rising trends toward authoritarianism and against democracy, at some point we’re faced with a sort of a moral test of what we’re willing to speak up about,” Wallace said during his presentation.

Wallace argues that, because people are inherently biased, their reporting always serves a particular interest. Whether a reporter’s words are upholding tradition or questioning dominant systems of power depends on the individual, according to the published author.

“All journalists are activists, in the sense that we’re making something more or less possible in the world by what stories we tell and how we tell them,” Wallace said. “For me, this act of storytelling, this act of documenting, was always about making my life and other people’s lives safer and more possible.”

According to Wallace, activism is an essential part of journalism. Still, he said, striving for delivering thorough and accurate reporting remains a priority. He further argued that abandoning the pretense of neutrality shouldn’t mean doing away with other long-held journalistic standards, such as rigorous research and factual backing.

“I think we all benefit a lot from the practices of rigor and meticulousness that are part of the story of how objectivity has been taught in journalism schools,” Wallace said. “The beating heart of journalism, for me, is still curiosity and openness.”

Julia Postell, a senior majoring in journalism, media management and criminology, believes journalists’ responsibility to their audiences requires that they be critical of what messages they are spreading.

“I think activism is so, so essential and holds a very strong place in journalism, because journalists are the voice of the public and have a major platform and duty to society to share what they believe is right or wrong,” said Postell.

Similarly, for Ph.D student and School of Communication professor Luis Garcia Conde, activism is a key part of the profession. In fact, according to Conde, a focus on “neutrality” in journalism is a largely American construct.

“Under the traditional idea of journalism, the extended American version that sees journalism as a non-partisan entity, there is no room for activism,” Conde said. “However, we have examples from other parts of the world that have shown that this view of journalism can be outdated. In Latin America, for instance, there are examples of journalism focused on giving a voice to historically marginalized groups.”

Conde, who also worked as a journalist in Mexico for over a decade, has long been used to incorporating social justice into his work.

“Professionally and personally, I reject the idea of objectivity, primarily because it stems from a misunderstanding of what journalism is,” Conde said.

Sandford Bohrer, lecturer at the School of Communication, agrees that there may be an issue with journalism in its current iteration, but maintains that the issue is greatly nuanced.

“[Activism] has a place, so long as it is identified as such,” Bohrer said. “I think the place for activist journalism is where [Wallace] described it: gender issues, race issues, environmental issues and generally issues relating to marginalized people who get under covered in more mainstream media. Social issues. Social justice.”

Still, according to Bohrer, neutrality may serve a purpose rebuilding trust among alienated audiences.

“The only real incentive is a desire to better society and do your part to rebuild trust,” Bohrer said. “I think trust is essential to any meaningful relationship, including one between the media and their audiences…I think neutrality can work, but not if we use that to ignore social issues and marginalized people. Neutrality to me means being fair, but that does not mean that opposing sides are equal in credibility or anything like that.”

The exact opposite may be true, according to Conde, who suggests that activist journalism may serve to bolster audience opinions of the media.

“The fact that people don’t trust the media or journalism has a significant historical context,” Conde said. “Historically, journalism has also aligned itself with powerful or oppressive institutions. I believe the potential solution to that is to build trust within the community, both on a small and large scale, and rebuild trust by involving and representing people.”

It is difficult to pinpoint, according to Conde, a single approach that may serve to resolve the tension between competing narratives of neutrality and activism. A reporter is better served, he said, by making the decision based on their personal beliefs of what may best serve their audience.

“Perhaps that question should be answered on a personal level,” Conde said. “There’s an old saying from the Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski that says to be a good journalist, you must first be a good person, so I believe the journalist’s first responsibility is to themselves.”