Etant Dupain is an independent journalist and filmmaker from Port-au-Prince, Haiti. He frequently collaborates with international media organizations like Al Jazeera, CNN and BBC. Back in 2015, Dupain wrote an article for Woy Magazine titled “Hats off to Madan Sara,” where he promised to make a film surrounding the network of women at the heart of Haiti’s informal economy. Five years later, on Nov. 21, 2020, I joined Dupain for the U.S. premiere of “Madan Sara.”

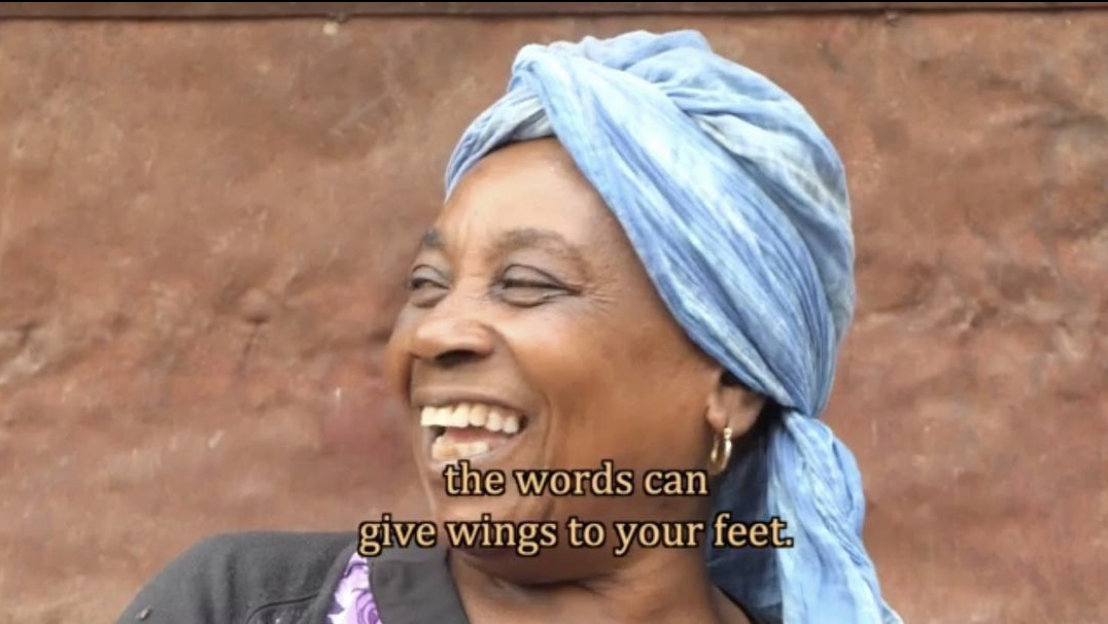

“Madan Sara” is a force to be reckoned with. It doe not ask permission to exist; it exists solely as one big cry for justice. It encapsulates the same spirit of fight and courage as its subject matter, the Madan Sara. The term comes from a migratory bird of the same name, known for its rather extreme measures in the protection of their young— a theme that is carried over in the film.

Over the years, international news has tainted the reputation of Haiti. It is embarrassing, but nonetheless important to admit, that before watching “Madan Sara,” I knew very little about the country. I knew about the political instability, the HIV epidemic and the 2010 earthquake. I knew about the migration to the Dominican Republic. I knew about the lack of jobs. I knew about its level of poverty.

Watching “Madan Sara” allows viewers to surpass their Euro-centric views and gain a greater understanding of the rich heritage of the Caribbean’s first independent nation. That, in part, is because the film touches on the very core of Haitian identity— a country whose spirit is synonymous with sacrifice and love.

On the surface, a Madan Sara is a woman that connects goods from the farming mountains of Haiti to consumers in the city. But really, the Madan Sara is a group of women that hold a nation on their shoulders as they fight against the struggles of their world. They are micro-entrepreneurs that hold a nation’s economy together. They work communally, sharing the profits and protecting each other from the dangers of political instability and social oppression, from everyday extortion, from debt-collectors, from government-plotted fires of markets, from rape and theft.

To be a Madan Sara is a matter of love. Despite the adversities, they work tirelessly to put their kids through school, provide them with housing and pave the way for a brighter generation.

The trade of the Madan Sara is almost exclusively dominated by women. From its inception, when Haiti was still a slave state, men were infamous for stealing goods and running away to freedom. It was the women that came back, cared for the children and helped the nation flourish.

Dupain himself is the son of a Madan Sara, from whom he inherited his spirit of courage and perseverance and spent close to a decade making the film. At times, it seemed like an impossible task, but what pushed him forward was the grit and dedication he learned from his people.

The following Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

TMH: First of all, I want to congratulate you personally. I can’t even imagine the difficulty of making this film and having the end result be something that’s so powerful. I was really touched, and I learned so much.

Dupain: Thank you man! I’m glad it had an impact.

TMH: Your film shows a deep love for your country. What does Haiti mean to you? And how did that story lead to the making of “Madan Sara?”

Dupain: Haiti is the Madan Sara. My mother used to sell mangoes in the markets, and, sometimes as a child, I would accompany her. I can’t tell you how much of an impact those markets have had on my life.

My mother taught me so much about hard work. She took care of five children. Similarly, I learned a lot about the Haitian economy in those markets about how extra hard these women worked to keep the economy running, to keep the country together.

When I became a journalist in Haiti, I knew I wanted to do something regarding the human rights aspect of the economy, to help relieve the pain that some of these Madan Sara were suffering daily. Then it clicked that I had to do a film about it. It was the only way their voices could be heard.

TMH: There’s a scene in the film about a kid named Oscar whose mother, a Madan Sara, buys him a camera so that his son could be a photographer. When I saw that scene, I also saw Etant Dupain getting his first camera. Can you tell me a little more about the subjects in your film?

Dupain: I got to be very close to the subjects in my film because it really took me my whole life to make. I left Haiti in 2007 to work abroad, and when I returned to Haiti in 2015, I had to reestablish some of those relationships.

I wanted the film to tell their stories, and the only way I could do that is if they trusted me. Often, media organizations come to Haiti to show the country in a bad light, and people don’t like that. But I was part of that environment, and it helped me a lot to really get into the personal lives of my subjects, like Oscar, for example. It makes me happy.

It’s not only me that has become something thanks to a Madan Sara, but a whole nation that is is growing because of the Madan Sara’s hard work.

TMH: The discussion following the film’s U.S. premiere dealt a lot with the concept of the poor portrayal of Haiti in big media. Was your vision for the film to be international? Was it to repair some of these misconceptions?

Dupain: The film was made for the people of Haiti, but I’m glad that the film has the ability to change how people perceive us. I crafted the film in such a way that, by itself, it could serve as a good introduction to outsiders.

International media puts all sorts of labels on Haiti that I think are rather unjust. I tried to make a story that was original. My approach was original, it wasn’t the typical way that a producer would make a film, and by being so personal, my intention was to make a film that educated the people of Haiti about themselves, about their role in society, about their mistreatment of Madan Sara, about a possible move forward. It’s a social film really.

TMH: By taking a different approach in the production, was the funding process of the film any different? For the filmmakers and documentarians at the University of Miami, where should we start?

Dupain: If I were to give any advice for students, it would be to have your first project be something you are really passionate about. Beyond anything else, it must be something that, when completed, it will be something you would be proud of.

It shouldn’t be about making a film; it should be about doing something that means something to you. After the premiere, I received so many letters and emails from people telling me how much the film had impacted them. By having this passion, no matter what adversities come in the way of the making of the film, it pushes you to complete it through.

Funding can be rough and demoralizing, and that’s why you have to have a project that you are dying to complete. For example, we ran out of funds before we could do the editing of the film, and I decided to do a Gofundme. We raised over $10,000 because people saw what we already had, and the donors believed in the project as much as I did. That money helped to hire a good editor and finish the film.

You have to be patient, and you can only be patient if you really believe in the project.

TMH: I know that you plan to do a tour in Haiti where you will be screening the film for free for different communities. Tell me a little more about that.

Dupain: It’s funny; I just returned from putting fliers announcing the tour. It goes back to the concept of being passionate about the project. Now that the film has grown into something larger than myself; we want to show it for free in different parts of Haiti to spark dialogue.

I think it’s time to rethink and have a different discussion about the way we treat women in Haiti, about the way we treat hard-working people. And the film is the beginning of that conversation. We have planned five different locations so far, and we want to do it during National Women’s History Month in March.

The real hard work starts now, with trying to have these discussions around these issues, because I truly believe that the clearest way forward for Haiti is if we listen to the Madan Sara and build an economy around them, with rights and protection. The film needs to be shown in the heart of Haiti; it needs to be shown to the people that need it the most.

TMH: In your recent conversation with the Film Bug Podcast, you mentioned that there’s no lack of stories to tell of Haiti. What’s next for Etant Dupain? Do you plan to continue making films in your homeland?

Dupain: The experience with the film has really sprung a series of ideas that I want to explore further. I’m currently writing something, and I will announce it when the time is due.

For the time being, my focus is on this tour and having the film serve its purpose in the community. All I know is that I want to follow this route of filmmaking, where stories are personal and have real-life implications. But my head is on the tour.

With the pandemic, I want to do this right, and have all the precautions and follow the rules. Traveling will be difficult, but we are confident that it will all come through. Either way, I think “Madan Sara” has gained a spot in Haitian film history, and I couldn’t be prouder than that.

Click here to learn more about Dupain and his work in Haiti and here to view the official “Madan Sara” trailer.