The University of Miami paid Manny Diaz, the former head football coach, a base salary of $3.4 million during the fiscal year ending in May, 2022. Between high profile football games and a passionate fan base, there’s little surprise that he was the University of Miami’s highest-paid employee.

The same goes for the third highest earner, Jim Larrañaga, the current head basketball coach who led the ‘Canes to the Elite Eight during the 2022 fiscal year.

Lesser known in the list of top earners though are three employees who make more than Julio Frenk, the UM president. All three are medical professors at UM, hold administrative roles in UHealth and made an average salary of $2.58 million in 2022.

For those unfamiliar with these numbers, it is not unusual to pay a doctor, especially a high-ranking one, this amount of money, nor for a doctor to double as a university professor. It is unusual however, that UM, foremost a university, pays them. For comparison, the highest 10 earners at nearby University of Florida are all top administrators for the university.

“That is pretty surprising. I would have assumed most of our money would be spent on academics at the university,” said Alex Miller, a junior studying microbiology and immunology with a minor in health management policy.

Over almost 70 years, UM has built a web of medical services, spanning from internationally renowned eye care to a comprehensive cancer center. In 2008, UM consolidated its network of university-based medical entities into the University of Miami Health System, also known as UHealth.

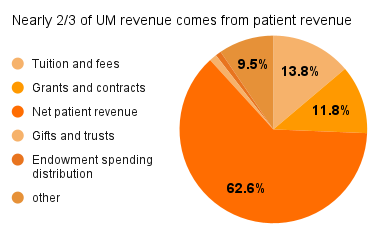

The relationship is unusual, and it shows in UM’s tax filings. In the fiscal year ending in May, 2022, UM had a revenue of $5.47 billion, the 12th highest of nonprofit universities in the U.S. according to ProPublica’s database. For reference, the nationally top-ranked Princeton University made less than that at $5.02 billion.

Yet, Princeton boasts a $35 billion endowment, contributing $3.33 billion to revenue made in 2022. That number dwarfs UM’s endowment.

UM’s ownership of UHealth helped it generate $2.94 billion of revenue just through healthcare services in 2022. UM could then spend $1.16 billion of its expenses on academia, nearly doubling what attendees paid for in tuition and fees.

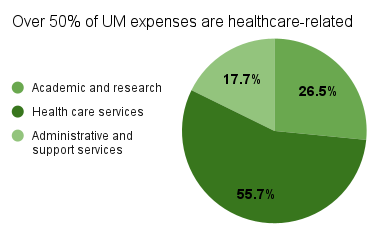

However, this $1.16 billion is only 26.5% of UM expenses. Over half of UM dollars were spent on health care services, a category that does not even exist for the majority of universities. Based on spending, UM is a health system first, then an academic institution.

Indeed, in UM’s mission statement to the Internal Revenue Service, it states, “Founded in 1925, the University owns and operates educational and research facilities as well as a health care system. Its mission is to educate and nurture students, to create knowledge through innovative research programs, to provide service to the community and beyond and to pursue excellence in health care.”

That final tenet has grown to become part of the core of UM operations since the inaugural class started at the Miller School of Medicine (MSoM) in 1952, then known as the University of Miami School of Medicine.

In the same year that the medical school began operations, Miami-Dade County established an official relationship with the University of Miami through Jackson Memorial Hospital (JMH). The facility is owned and operated by the county, but UM provides all medical teaching and most training and care through its medical faculty. JMH has existed alongside the development of UHealth as another outlet for academically-oriented doctors.

Dr. Yehuda Raveh, an anesthesiologist at JMH and associate professor of clinical anesthesiology at MSoM, is one of the many who has worked as a professor and clinician at UM and JMH respectively.

“I was interested in academic work,” he said. “And because that’s what I like, I did not seek to go to a private practice.”

He noted that the financial compensation at a private practice may be higher, but the University offers “wonderful benefits,” including tuition assistance for his children and health benefits. His job also builds academic work into his weekly schedule, allowing him to stay engaged in education.

Within Raveh’s contract, one of every five days is devoted to administrative duties, which includes teaching.

“We do the whole teaching, the actual management of the patient, how we sedate the patient, monitor the patient, how we handle the airway, how we do the intubation. They sometimes get to participate with the procedure if they already saw,” Raveh said.

On the clinical days as well, Raveh is continually teaching and training residents and nurses. As a still practicing doctor, Raveh can help advise students in their medical careers, specifically as it pertains to anesthesiology.

According to Raveh, the education done through JMH provides an important opportunity for medical students to learn how medicine works beyond the classroom. At the financial level, the only nod towards JMH is a section in the audit that says the agreement between UM and the county contains terms for “mutual reimbursement of services.” Regardless of how much money, if any, that JMH contributes to the university, its role in teaching has a value of its own in the academic sphere of the university.

“The more experience you have, the more knowledgeable you are, that’s natural, and you have maybe a wider horizon about changes and where medicine is going,” Raveh said. “We are teaching as we work because that’s what they learn, medicine.”