The United Nations Security Council started off the first week of October with a successful vote to deploy military forces, led by Kenya, on a mission to counter violent gang activity in Haiti.

The mission is a response to the countless calls for international support from the Haitian government as the terrorizing nature of the gangs has made it difficult for the Haitian National Police (HNP) to maintain peace.

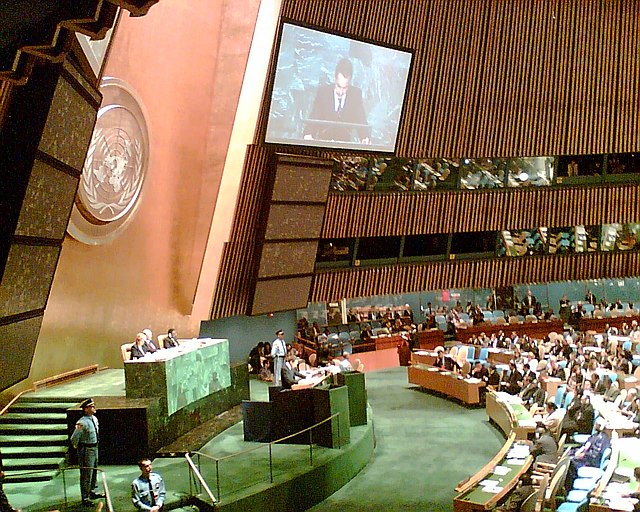

The mission, Resolution 2699 (2023), was adopted on Monday, Oct. 2. Thirteen nations voted in favor, while China and the Russian Federation abstained.

Prime Minister Ariel Henry of Haiti made his final plea for military aid in late September, reiterating the intensity of the humanitarian crisis.

“In the name of the women and girls raped every day, the thousands of families driven from their homes, the children and young people of Haiti, who have been denied the right to education and instruction, in the name of all a people who are victims of the barbarity of gangs, I urge the international community to act quickly,” Henry said in an address to the UN General Assembly’s 78th session.

Foreign Prime Minister of Kenya, Alfred Mutua, is promising to deploy 1,000 police officers to aid in the stabilization of peace in Haiti, along with training and equipping the HNP with better peacekeeping strategies.

The mission is set to take place over a 12-month period, with a review after nine months by the Security Council. It will be supported by voluntary funds, with the United States pledging $100 million to the Kenyan-led force.

Gang violence in the Caribbean country has displaced upwards of 200,000 residents, and has been responsible for the death of 3,000 and the kidnappings of 1,500 Haitians this year alone.

“Seeing it, it’s really sad. I’ve never been to Haiti, so that’s always been a goal of mine. Hopefully at some point I’ll be able to go, I really want to see where my parents grew up and everything,” said Brandon Mirvil, senior music composition major and member of the Haitian community at UM.

Though most attacks are at random, a significant portion of those targeted are women and children, who are raped and tortured as they are held for ransom.

The number of Haitians that fall victim to gang violence continues to grow without international intervention.

“Whether or not this resolution will solve the current security problems plaguing Haiti remains to be seen, especially given that the outside police forces are not expected to arrive on the ground until early 2024,” said professor of international studies John Twichell. “However, it must be considered a step in a more favorable direction for the peoples of Haiti in normative terms.”

The reasoning behind the vigilante movement is a fight for control of Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince.

Gangs currently control an estimated 80% of the capital, with the primary gangs being G-PEP and G-9. There is constant conflict between the two groups in a fight for power in Port-au-Prince, with residents held hostage in their homes as ceaseless shootouts fill the streets.

With the country’s economic instability, inadequate healthcare system and food insecurity that is one of the highest levels in the world, Haitians are perpetually unsupported by their government, leaving them increasingly vulnerable to gang violence.

“In the case of Haiti, we see an incapable government under immense pressure to hold a presidential election to restore some semblance of national political legitimacy, yet violent gangs and other organized criminals impede this process because democracy would be contrary to their own criminal interests.” Twichell said.

Gangs have a long-standing presence in the Caribbean country, with the earliest inklings of organized crime groups emerging during the reign of populist dictator François “Papa Doc” Duvalier in the 1960’s.

The latest uptick in gang violence in Haiti is correlated with the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in 2021. Today, there are no elected government officials left in the nation.

“If the UN doesn’t do anything, it’ll just stay the same – more murders, more kidnappings – we really need to take this out of Haiti, so I’m really glad that at least something is being implemented.” Mirvil said.

Kenya stepped up to lead the mission’s multinational forces in July 2023, when UN discussion on the matter was still in its introductory stages despite the Haitian Prime Minister making his first plea in October 2022.

Although the resolution maintains multinational support as well as backing by the Haitian government, critics in both Kenya and Haiti have expressed concern over the mission.

In Haiti, a past history of sexual abuse and contribution to a deadly cholera breakout following a 2004 UN peacekeeping mission leaves some Haitians skeptical of the foreign aid.

In Kenya, some opposition lawmakers argue that it is a violation of the Kenyan Constitution to bypass parliament approval of the mission before sending officers.

However, local Haitians have reflected a cautiously-hopeful sentiment following announcement of the mission, expressing how international support is their only option.

“From an outside point of view it’s really sad, but I know we will make a change. It’ll get better,” Mirvil said.