A teach-in is not the same as a protest. That’s the first message organizers wanted their audience to understand.

The event, a midday gathering on Tuesday, April 25 titled “What’s going on?!” featured an array of University of Miami professors educating on House Bill 999 through the lens of their particular disciplines.

Rather than rallying against the bill, the teach-in was framed as an educational event, designed to showcase a diverse range of perspectives and create a forum for discussions and Q&A’s.

HB 999 has drawn controversy across the state and UM, as The Miami Hurricane has reported, for its broad restrictions on education. The bill especially focuses on content related to DEI (Diversity, Equity and Inclusion), Critical Theory and LGBTQ studies at public Florida universities.

While UM professors would not see their classroom content affected, the bill would impact the broader education community in Florida.

The bill, large in scope and in the midst of ongoing updates, has spurred confusion and misinterpretations, due in part to its somewhat vague nature.

“Everybody’s talking about this stuff and somehow it seems a lot of people are saying pretty different things,” said Dominique Reill, the moderator for the teach-in, a professor of modern European history at UM and former director of Undergraduate Studies.

The teach-in was set to remedy that.

Professors have spearheaded similar events before, especially before COVID-19. Just last year, faculty hosted a teach-in on the escalation of the Russian-Ukraine war. Tuesday’s event distinguished itself though by its emphasis on discussion as opposed to lecture-style education.

Each speaker only received five minutes, keeping their remarks to about 750 words. Interspersed throughout, audience members had the opportunity to ask questions.

These are five key takeaways from the speakers at Tuesday’s teach-in:

These takeaways are not a reflection of The Miami Hurricane’s viewpoints or interpretation of the legislation, but rather of the information that was shared at Tuesday’s teach-in.

Recent Florida legislation is foundational to Florida education

With little recent precedent in Florida and overarching implications, Florida legislation is laying the groundwork for “intrusion into educational institutions,” according to Assoc. Dean of Intellectual Life at UM’s law school Charlton Copeland.

He said the state government has laid the groundwork by identifying two prominent “boogey men,” issues around race and around diversity, to justify the legislation. These are prominent issues that feature in HB 999’s initiatives and other well-known legislation, such as HB 7, colloquially known as the Stop WOKE Act.

“It is a fundamental re-allocation of authority inside of higher educational institutions,” Copeland said in reference to HB 999.

He also noted the concentration of hiring authority to the public university’s president, exclusion of identity politics in the hiring process and the introduction of a post-tenure review every five years.

“This is the train that the destruction of American higher education is riding in Florida,” Copeland said.

HB 999’s language undermines intellectual freedom

“If you listen closely to the language of both of these bills, they make very clear statements about whose feelings matter and whose values are worthy of being passed on,” said Marina Magloire, an assistant professor of English at UM.

She described coded language that followed the assumption that “white people have earned their power fair and square, and that people of color are only held back by our own laziness and lack of moral fortitude.”

In HB 999, the Florida Board of Governors would have the power to review any curriculum based on theories that “systemic racism, sexism, oppression or privilege are inherited in the institutions of the United States, and were created to maintain social, political or economic inequity.”

The bill also touts the importance of a Western Canon, otherwise known as classical American literature.

The bill prioritizes this type of literature over others.

HB 999 will affect graduate students at UM

The bill’s banning of DEI initiatives hinders the work of graduate students in their respective fields, according to Tarika Sankar, a PhD student and former president of the Graduate Student Association.

She referenced graduate students in biology and at UM’s Rosenstiel school who have focused on advocating for increased representation of marginalized communities in their respective fields. HB 999 dismantles this work through its focus on hiring processes. Legislation restricting DEI initiatives at the student level will eventually affect the faculty as these graduate students attempt to enter teaching.

Particularly in Florida, Sankar said graduate students would be less likely to choose to study in Florida. She referenced multiple PhD colleagues who had declined job offers in Florida for this reason.

Morgan Gianola, a postdoctoral scholar at UM in behavioral medicine and cardiovascular diseases in the psychology department, referenced her research as being vulnerable to the legislation.

“Our lab does work in health disparities across different communities, and we can’t study or talk about health disparities without talking about systemic racism, without talking about environmental justice, without speaking to the things that this bill is specifically trying to silence,” Gianola said.

These laws and bills erode the American liberal tradition of viewpoint diversity

“Without establishing false equivalencies, do we really want to go down a road of idea suppression, that is not too dissimilar from the very practices of unfreedom that we so often criticize elsewhere in the world, especially from Miami,” said Michael Bustamante, a history professor at UM and historian of the Cuban revolution, exile and diaspora.

Bustamante described a Cuba with “brilliant” scholars, scientists, students, writers and artists stifled by idea suppression.

He also described his own commitment to a “willingness to respect, to engage, to debate points of view different from one’s own, so long as they respect the dignity and points of view of others.”

The language used in HB 999 specifically defies this value, according to Bustamante, outright banning some degree programs and entire concepts.

He prefers to challenge students’ viewpoints in his own class, playing devil’s advocate when appropriate. Bustamante sees no use in offering students “confirmation bias” as they could find this elsewhere easily.

UM faculty would have to heavily redact their syllabus if UM were regulated by HB 999

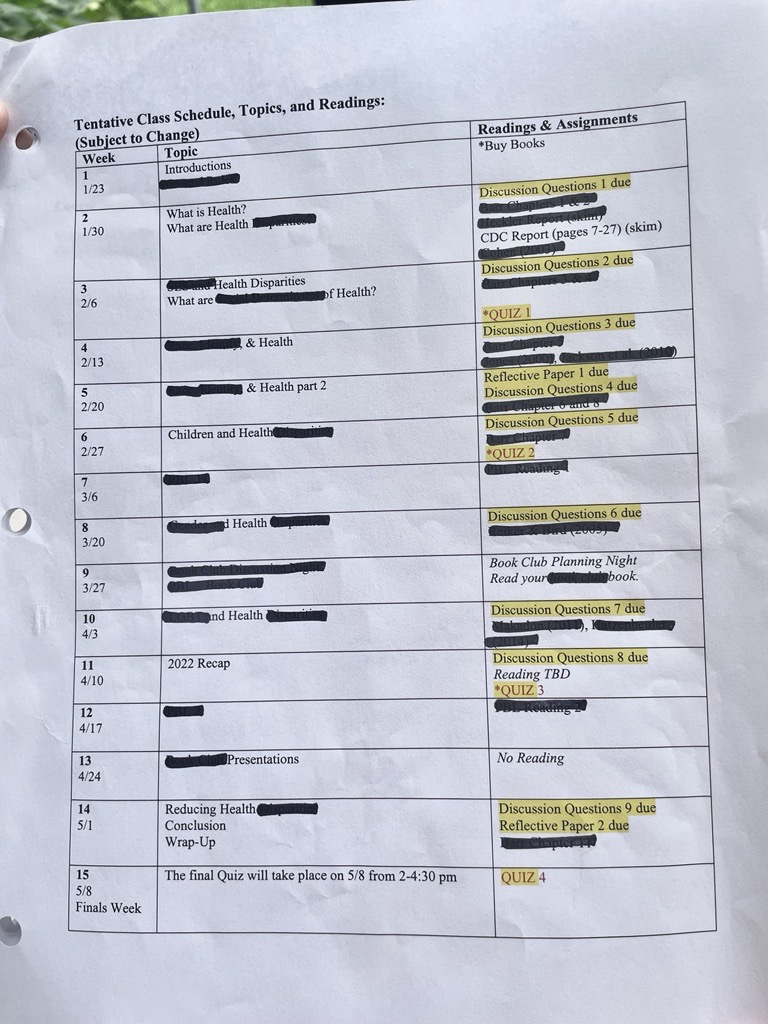

Andrew Porter, an associate professor in UM’s School of Nursing, held up a heavily marked-up syllabus and reading list for audience members.

While HB 999 would not affect any of UM’s educational content, Porter simulated his own curriculum as if it did. The result was striking with nearly half of words and phrases blacked out.

Porter’s studies focus on sex and health disparities, where some of its concepts are directly prohibited in HB 999. As a professor, he teaches the future nurses, doctors, health professionals and health interventionalists, but couldn’t educate them properly if he followed HB 999’s guidelines.

“You’re marginalizing populations, especially LGBTQ populations that are already the most vulnerable people in our state,” Porter said. “Whenever you weaponize someone’s identity, whenever you turn someone’s identity into a political beating stick, there’s pretty significant negative mental and physical health consequences.”