On second and goal 11 minutes into the first half, University of Miami quarterback Malik Rosier lofted it up to the back right corner of the end zone, where wide receiver Braxton Barrios hauled it in for the first touchdown of the game.

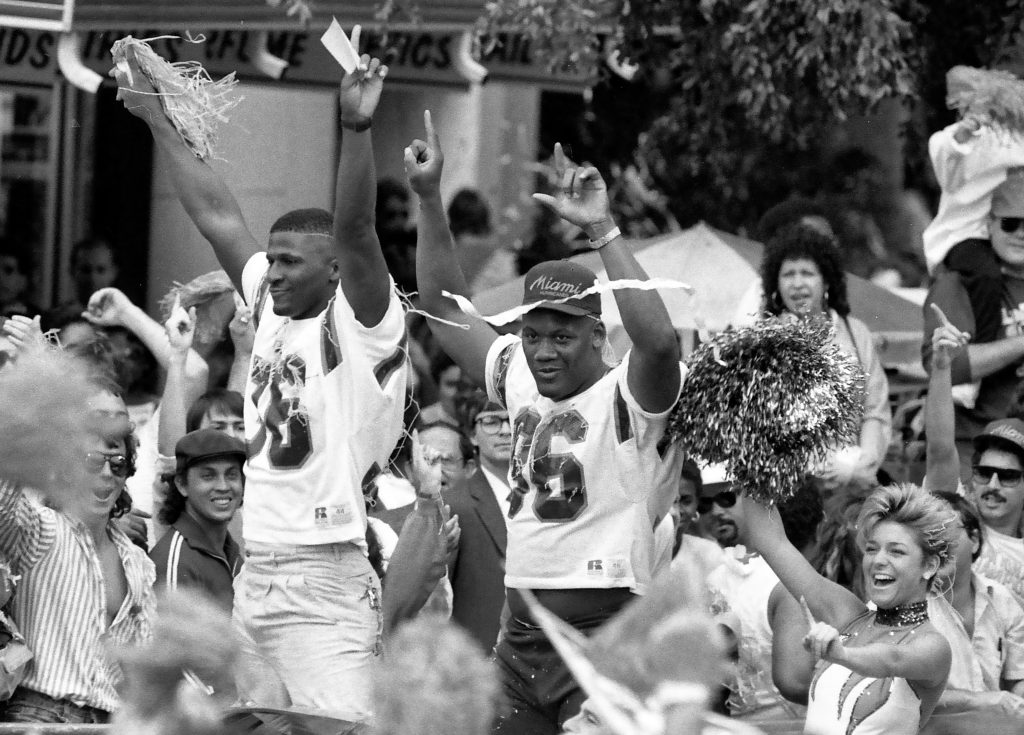

The packed crowd at Hard Rock Stadium erupted with deafening power.

Less than a minute later, Jaquan Johnson caught a tipped pass for UM’s first interception of the night.

What was supposed to be a top 10 showdown of the 2017 season between No. 7 Miami and No. 3 Notre Dame ended up a 41-8 thrashing by the Hurricanes.

“That stadium, Hard Rock, was almost as loud as the Orange Bowl, and it was really close to as loud as the 1989 national championship game,” said Susana Alvarez, a senior lecturer in the Miami Herbert Business School. “It was crazy. The energy was there and of course that’s going to power up our players. They are unstoppable if you have a full stadium, right?”

For many Canes football fans, the blowout win was the last time they witnessed a sold out crowd at Hard Rock Stadium.

Since the 2017 season, when UM finished with a 10-3 record and went on to lose to Clemson 38-3 in the Atlantic Coast Conference championship game, Miami has gone 7-6 in 2018, 6-7 in 2019 and 8-3 in 2020.

The Canes’ best record under Manny Diaz was 2019’s 8-3 season, which some fans considered a strong performance. But long-time Miami fans have reached the top of the mountain. They know what that rare air feels like. And they won’t be satisfied with anything less.

1983 to 1993 was UM’s “decade of dominance,” said Harry Rothwell, owner of allCanes, a University of Miami fan shop located on Ponce de Leon next to the Coral Gables campus. In those years, Miami won four national championships, lost two and were in the mix for two others.

“Not even Alabama today can say they are that good,” Rothwell said.

Miami won their fifth national championship in 2001 under head coach Larry Coker.

“I’ve witnessed all the national championships from ‘83 on, and I tell people all the time, I’ve seen the best of the best and if I never saw them win again, I couldn’t hold it against them, because there’s not many programs that have won a national title, not to mention five,” Rothwell said.

But Miami’s years of football dominance are now a thing of the past, and fans have responded to the program’s failures with nothing short of animosity.

“What other fans hire an airplane to circle around the stadium saying fire the coach?” said Susan Mullane, a professor in the department of education who has been at UM since the 1970s.

The problem with being as good as the Hurricanes were for as long as they were is that anything short of competing for a national title now feels like a failure.

But things have changed since the glory days.

For starters, Hard Rock Stadium is a far cry from the Orange Bowl, the former home stadium of the Miami Hurricanes, located in Little Havana.

“That was our stadium and in losing that stadium, we lost the students wanting to go out to football games,” Alvarez said. “It became a chore to go all the way up to Miami Gardens.”

For UM students looking for instant gratification, and living in a city like Miami where entertainment options are endless, traveling 45 minutes to Hard Rock without a guarantee Miami will win has become a chore.

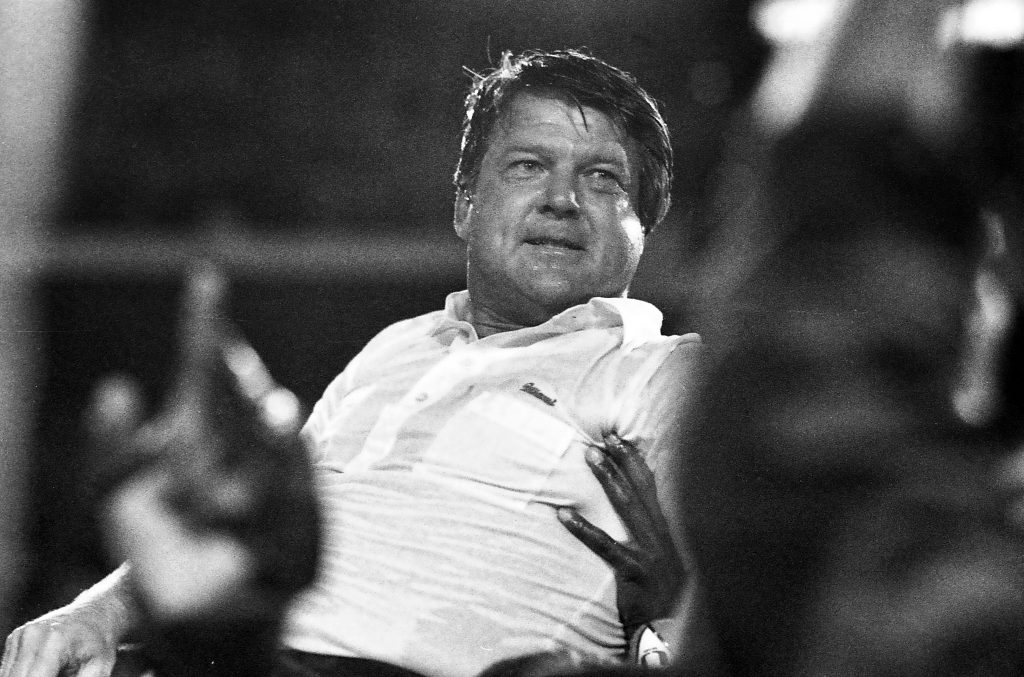

Problems with recruiting have accelerated Miami’s fall, with universities now recognizing the immense wealth of high-school football talent in South Florida. When Howard Schellenberger came to UM as head coach in 1979, he upped the program’s recruiting efforts in South Florida by declaring Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm-Beach counties the “State of Miami.” Jimmy Johnson, head coach from 1984-1988, made a point to continue what Schellenberger started.

But competition has stiffened, as every Division I program now recruits players from South Florida.

“If you are a guy coming from Palmetto, South Dade, Northwestern or Central and Nick Saban flies a helicopter to your field and asks you to play football for him, I mean that’s pretty impressive,” Rothwell said.

The fact is that many other college football programs have become more attractive to potential recruits, with better fan bases, better facilities and more money to work with, not to mention recent success.

“I laugh when people say President Shalala didn’t care about football,” Rothwell said. “They do care about it, but they also care about their business school, their medical school, and the law school. All of them have budgets and expectations.”

As a private school with 11,000 undergraduate students, Miami’s financial situation is vastly different from most of the larger, public institutions that are consistently at the top of college football.

“I think if we could let loose the purse strings and everybody could do what they want, we probably could be back there,” Mullane said. “But we’re trying to look at Alabama, do you know anything about Alabama’s academic reputation, that people don’t go there for that.”

Analysts have said that problems with the program’s fan base, facilities and financial situation stem from a disconnect between administration, the athletic department and the coaches and players.

“You have an athletic department that clearly is not really showing that this is something that they are willing to try to make changes,” said ESPN analyst Kirk Herbstreit, reporting on College GameDay Saturday morning. “You look at the powerhouse programs, Alabama, Clemson, Ohio State – president, AD, head coach – same vision. They are aligned in their vision for what needs to happen – recruiting, budget staff, that’s what it takes. Miami doesn’t have that.”

Since 2006, Miami has averaged a 7-5 season and has had five different head coaches, with the constant turnover contributing to a decade of mediocrity.

“It has to be a perfect picture,” Alvarez said. “All those things have to fall into place and full commitment from the fans, from the players, full commitment from the coaching staff, from the administration. And then it clicks. And then it just becomes a machine.”