By Naomi Feinstein

A group of University of Miami students, alumni, and staff collaborated to investigate UM’s history on race relations. In doing so, the group uncovered troubling findings regarding the namesake of the Solomon G. Merrick Building, the oldest building on campus, and created a petition to rename the building.

“We demand the immediate removal of the Merrick name from the university’s School of Education building and all other university structures and properties,” the letter and petition read. 2006 UM graduate Evan Kissner created the petition around a month ago.

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests across the nation, many are calling for the removal of Confederate statues and flags and names of racial segregationists on buildings. Back in June, Princeton University vowed to remove Woodrow Wilson’s name from the school’s Public Policy building due to his segregationist policies as the 28th U.S. president, including resegregating aspects of the federal government. In Gainesville, Kent Fuchs, president of the University of Florida, announced on June 18 the school will no longer use the “Gator Bait” chant at its sporting events because of racist imagery associated with the phrase.

The student’s petition, which has more than 1,500 signatures, requests written confirmation from the UM administration and Board of Trustees that all facilities named after racists, segregationists and slave-owners will be renamed. The petition proposes forming an independent committee to represent the interests of students, alumni, faculty, administrators and Miami-Dade County residents.

“Working with local Miami-based historians, our group investigated Merrick’s past and discovered much evidence confirming that George E. Merrick boldly held and acted upon, racist segregationist beliefs throughout his life, including in his role as head of the Miami-Dade Planning Board,” the group’s petition reads.

Although the building is named after George Merrick’s father Solomon Merrick, George Merrick, who was celebrated as one of the founders of the university and the city of Coral Gables, made racist remarks and advocated for racist policies throughout his career developing the city of Miami. Therefore, the students say this building despite being named after Solomon is still connected to his son George and should be renamed.

The Merrick name is evident throughout the campus from the Merrick Garage to George E. Merrick Street. The name served as a reminder of the university’s past in dealing with race relations in the surrounding communities, but now, senior and president of the NAACP on campus Miles Pendleton says this is the time for the university to ensure the campus reflects the appropriate ideals of today.

“If we continue to foster the presence of that kind of history at our university, then that tells us where we really put our values and our importance in the direction which the University of Miami is choosing to move going forward,” said Pendleton.

During the land boom of the 1920s, George Merrick’s real estate legacy would unfold. George Merrick inherited 3,000 acres of citrus groves from his father. After studying the City Beautiful movement, George Merrick designed and developed a new town, which would eventually become Coral Gables, with an aesthetic similar to one of Mediterranean cities.

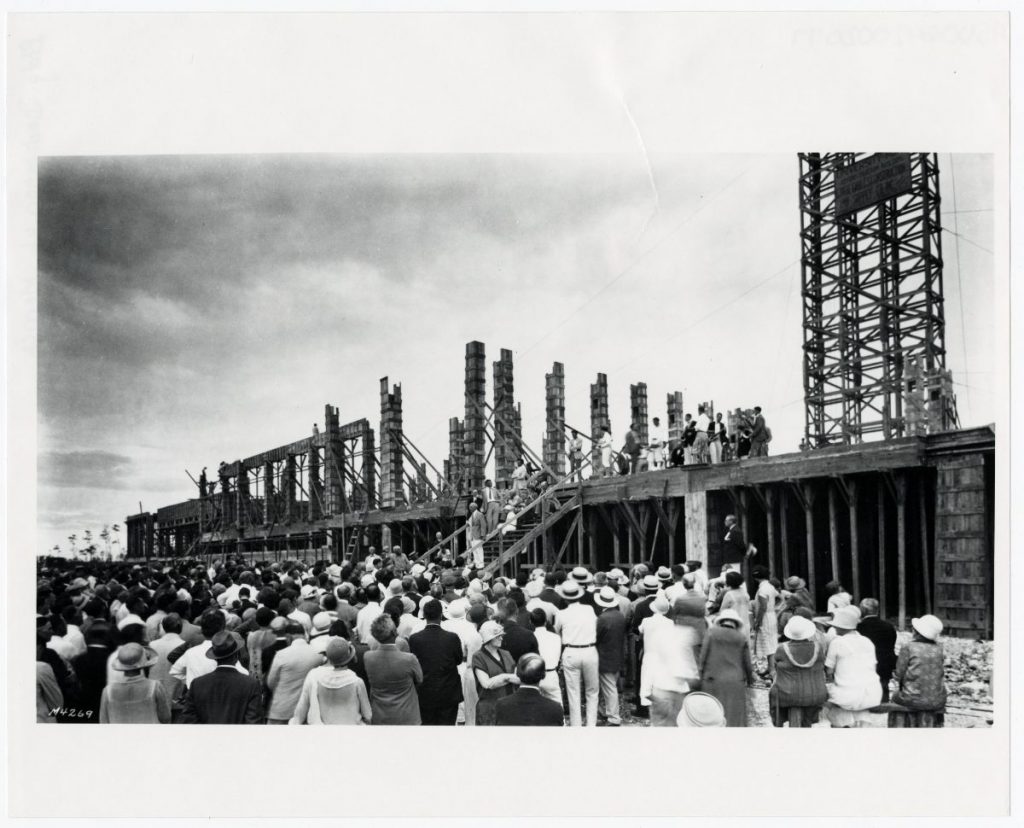

To help construct the university in 1925, George Merrick donated 600 acres and $5 million. He wanted to build the first building in honor of his father, but the building would not be completed until 1949 after his death. Thus, after speaking to historians, the students contend Merrick building serves to honor George Merrick and his father.

“It was Merrick’s intent to name it after Solomon, so it wasn’t just the university. He idolized his father,” said Pendleton. “Regardless of who it is actually named for, we still recognize that it is in conjunction with their relationship to this individual.”

Despite these accomplishments, George Merrick’s other work would taint his past. Throughout the 1900s, government officials worked to create racially segregated housing in Miami-Dade County. There would be a “color line” separating Black and white residents in an effort to keep the Black community limited to only a certain section of the city.

In 1936, the Dade County Commission approved a “Negro resettlement plan,” which sought to remove Black residents from Overtown to three distinct locations in West-Miami Dade to allow for white families to move in. George Merrick advocated in favor of this plan.

While serving as the chairman of the Dade County Planning Board, George Merrick said before the Miami Board of Realtors that the removal of Black residents would be fundamental to achieving the goals for the rest of Miami.

Additionally, the group of students uncovered racially fueled advertisements that were used throughout Miami to help gain support for the plan to evict the Black population to separate communities, which George Merrick proposed years earlier. These included caricatures and sayings, such as “Remove the monster,” and “We have tolerated our disgraceful slums for twenty years.”

The plan, however, was never implemented, but the idea of separating white and Black people still remained, contributing to developing other racially based housing development plans. According to author Raymond Mohl, subsequent policies included redlining and construction of the interstate highway, which ultimately would run through Black dominated communities

After reviewing the information compiled, many students voiced their support of the petition all over social media, calling for the university to stop honoring figures with racist beliefs.

“I think it’s incredibly important that we as a university, and a nation, stop memorializing and idolizing racist figures from our history,” said senior Kinnon McGrath. “Upon reviewing the articles and letters compiled by university leaders, of course, I chose to support this petition.”

While removing names of figures with racist connections is a step in addressing the university’s role in race relations, Tywan Martin, a Black associate professor in the department of kinesiology and sports sciences, said he doesn’t want to see any more symbolic gestures, but rather he hopes to see the university take an active role in fighting inequalities on campus.

“If you remove the name, that is just the start,” said Martin, president of the Woodson-Williams-Marshall Association, an organization for Black faculty and staff. “Now, you have to do the work in addressing it.”

Reflecting upon his experience teaching at Indiana University in Bloomington, Martin said he remembers there was a debate removing a mural depicting the Ku Klux Klan from an undergraduate classroom. He said his mentor proposed keeping the mural up to serve as a teaching moment and not allow the university to hide its history.

“It is in plain sight in terms of their thoughts, and it cannot be hidden in the archives that these types of ideas were welcomed on campus,” Martin said. The school’s officials kept the mural up, but they announced the room will not be used as a classroom.

Thus, Martin proposes the university keep the Merrick name on campus to educate students, faculty and staff about the university’s past in equity and inclusion.

“Keep it up there, but the university has to make it part of its fabric and will educate and train people on the issue,” Martin said. “I don’t want a plaque — it should be in bright lights.”

However, not only is the Merrick family name celebrated on the UM campus, but also throughout the city of Coral Gables, including Merrick Park, a luxury shopping mall, and the Merrick House, the former childhood home of George Merrick which now serves as a museum filled with Merrick family art and personal items.

Removing the Merrick name immediately, Pendleton said, would highlight the university’s intent in bringing about effective change and holding historic figures with racist pasts accountable.

“It also represents at our University of Miami that no one is above decency and morality,” said Pendleton. “As Merrick is such a titanic figure, if we can show the world, the community and our university that even he is not above the standard or degree to which we hold ourselves in this present moment then that means no one is.”

The petition and the group’s research were presented to the university’s administration and Board of Trustees on Monday, July 20, to start the conversation over renaming the building.

“The University is proud of the progress that has been made in all areas but realizes much work remains to be done,” according to a statement by the University of Miami. “The University of Miami is committed to improving all aspects of these values, and we welcome everyone in the University of Miami community to join the conversation.”