Sci-fi thriller “Ex Machina“ asks incisive questions without relying on flashy action. With only three speaking roles, the script uses implied dialogue to escalate suspense. While the characters rarely say what they mean, every word in the film has a purpose.

Eternally with vodka or wheatgrass in hand, Nathan (Oscar Isaac), a straight-talking genius millionaire, drunkenly admires his art piece, a graffiti-looking masterpiece by painter Jackson Pollock. The challenge of the painter, he says, was to not be intimidated by the repercussions of his actions while also allowing his subconscious to control his movements. Quiet intellectual coder, Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) who won a stay at Nathan’s eclectic wilderness house, agrees as usual, but this time it goes beyond the polite behavior of a guest.

Their discussion cheekily applies a double meaning to the film itself. Even small, humanizing characterizations, like Nathan’s party-animal tendencies and Caleb’s orphanhood, resurface to play pivotal roles in the plot itself.

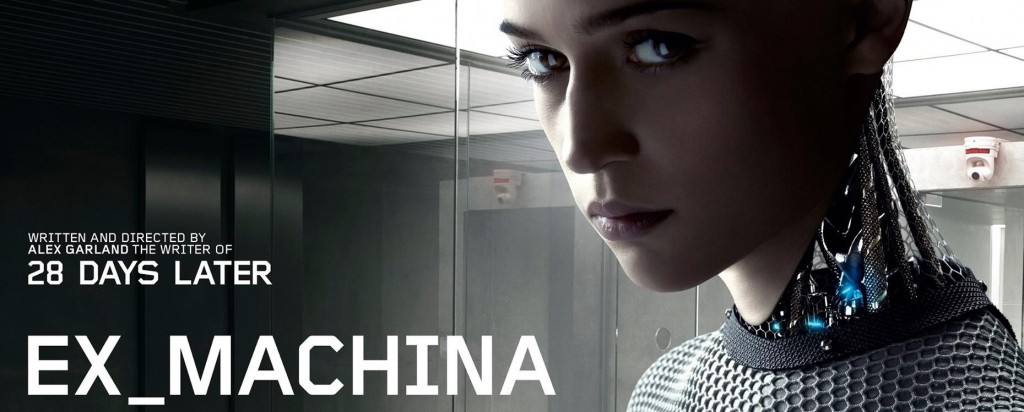

The simple plot is divided neatly by title-frames that number the scenes into encounters, with each consisting of Caleb’s witty interactions with the lifelike robot, Ava (Alicia Vikander). The chapter-like divisions hint at the writer-director’s background as a novelist.

As both the writer and director, Alex Garland rightly calls his film an “ideas movie”– ideas which he modestly says he “encountered through reading or sort of studying in one way or another.”

His script deftly builds conversations with the non-human, which peeks at precisely what it means to be human. While the plot itself is uncomplicated, its inferences and interpretability are profound. The film surprises with unexpected, bubbling twists that mock the plot’s simplicity.

It explores timeless themes like the blind trust of fake love and employee-employer pressure. It questions the treatment of automated life forms as disposable and parodies the lone-partier attitude and self-absorption of the Silicon Valley elite.

To both alleviate and intensify the difficulty of these questions, the film triggers uncomfortable laughs in strategically wrong places. Menacing actions are accompanied by childlike smiles; sadistic glares are contrasted by relaxing words.

Though unsubtle in its commentaries, “Ex Machina“ glows in its believable questioning on the future of automated intelligence. Unconfined by the limited set space within Nathan’s eclectic, streamlined laboratory home, it tackles hard questions like the morality, sexuality and self-awareness of sentient machines.