Nick Gangemi // Assistant Photo Editor

While some may be thrilled about the University of Miami’s new eateries, students and faculty in the psychology department are more excited about a different addition to campus – a magnet that is 60,000 times stronger than the Earth’s magnetic field.

The magnet is the main component of UM’s new Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) scanner, which was delivered in May to the recently built Neuroscience Building adjacent to the Cox Science Center.

Access to the scanner, which produces thousands of images of a subject’s brain in a matter of minutes, means that researchers at UM now have an invaluable tool for answering some of the hardest questions about human behavior and the brain.

“For people like me, you don’t just see the machine,” said Travis Evans, a first-year graduate student who is currently training to use the fMRI scanner. “You see all the possibilities of research questions you could answer.”

Evans will be working with Jennifer Britton, an associate professor who came to UM to run fMRI studies. They will utilize fMRI data to study anxiety disorders and fear conditioning in children and adults.

What sets fMRI apart is its ability to move beyond anatomy to actual brain function, allowing researchers to get a vital glimpse at the brain in action.

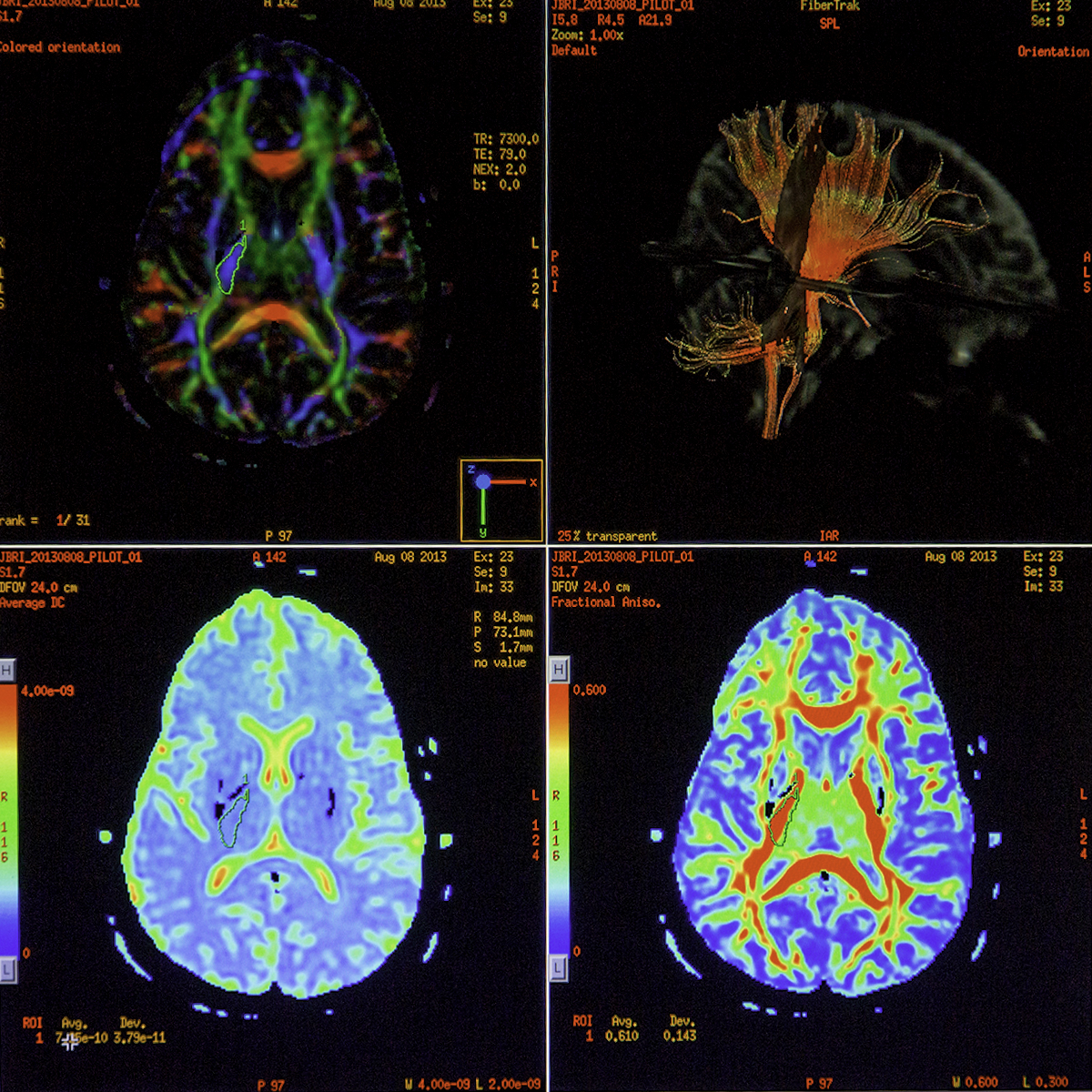

Subjects receive stimuli or perform tasks – such as determining an emotion on a face – and associated parts of the brain light up based on changes in blood flow, showing which parts of the brain are most active. It can also show how different parts of the brain interact and connect.

“Using those techniques, you can get at things like cognitive function, emotion, memory, language processing, thinking,” said Philip McCabe, associate chair of the psychology department. “These were higher order things that no one could really get at before.”

The scanner is now up and running after several tests by Pradip Pattany, research associate professor of radiology at the Miller School of Medicine. Currently, there are two faculty members ready to use fMRI in their research, and students working with them will learn how to analyze and interpret the scans.

Access is currently restricted to select graduate and postdoctoral students who are working with researchers, but McCabe said there might be more opportunities for undergraduates in the next couple years. One possibility is a neuroimaging class where students would work with fMRI data.

Regardless of academic status, anyone interacting with the scanner must undergo safety training. The scanner is potentially very dangerous, because metal – including metal within the body – will be sucked to the magnet.

“The magnet is always on, so it’s not like you can just walk in there,” Britton said. “There are deaths caused by not understanding that you can’t bring metal in.”

In addition to the magnetic scanner, there is a mock scanner to help subjects acclimate to the experience of having an fMRI, as well as a waiting room, dressing room and bathroom. Technicians and researchers operate the machine from a separate, shielded room where they observe through a window and communicate via microphone. Images from the scanner come up on a monitor.

Britton said that processing those images is a very technically sophisticated process that brings together physicists, psychologists, neuroscientists and computer scientists.

“You’ll see in the news these nice, pretty pictures of brains, but there’s a lot that goes into that,” Britton said.

Rod Wellens, chair of the psychology department, traveled to other universities like the University of Texas and the University of Southern California to look at how they funded and operated their fMRI research facilities.

When Evans was choosing a program, the fact that UM has an fMRI scanner completely dedicated to neuroscience research caught his attention.

“A lot of places I looked at split time on the machine with the medical school,” he said. “You’re basically fighting for crumbs of time. Here, this is our scanner that we get to use. A lot of programs don’t have that.”